Apache is the collective name for several

culturally related groups of

Native Americans in the United States.

These

indigenous peoples of

North America speak a

Southern Athabaskan (Apachean) language, and are related linguistically to the

Athabaskan speakers of

Alaska and western

Canada. The modern term Apache excludes the related

Navajo people. However, the Navajo and the other Apache groups are clearly related through culture and language and thus are considered

Apachean. Apachean peoples formerly ranged over eastern

Arizona, northwestern

Mexico,

New Mexico, parts of

Texas, and a small group on the plains.

There was little political unity among the Apachean groups. The groups spoke 7 different languages. The current division of Apachean groups includes the

Navajo,

Western Apache,

Chiricahua,

Mescalero,

Jicarilla,

Lipan, and

Plains Apache (formerly Kiowa-Apache). Apache groups are now in Oklahoma and Texas and on reservations in Arizona and New Mexico. The Navajo reside on a large reservation in the United States. Some Apacheans have moved to large metropolitan areas, such as New York City.

The Apachean tribes were historically very powerful, constantly at enmity with the

Spaniards and

Mexicans for centuries. The first Apache raids on

Sonora appear to have taken place during the late 17th century. The

U.S. Army, in their various confrontations, found them to be fierce

warriors and skillful strategists.

The warfare between Apachean peoples and Euro-Americans has led to a stereotypical focus on certain aspects of Apachean cultures that are often distorted through misperception as noted by anthropologist Keith Basso (1983: 462):

"Of the hundreds of peoples that lived and flourished in native North America, few have been so consistently misrepresented as the Apacheans of Arizona and New Mexico. Glorified by novelists, sensationalized by historians, and distorted beyond credulity by commercial film makers, the popular image of 'the Apache' — a brutish, terrifying semihuman bent upon wanton death and destruction — is almost entirely a product of irresponsible caricature and exaggeration. Indeed, there can be little doubt that the Apache has been transformed from a native American into an American legend, the fanciful and fallacious creation of a non-Indian citizenry whose inability to recognize the massive treachery of ethnic and cultural stereotypes has been matched only by its willingness to sustain and inflate them."

Name and synonymy The word

Apache entered English via Spanish, but the ultimate origin is uncertain. The first known written record in Spanish is by

Juan de Oñate in 1598. The most widely accepted origin theory suggests it was borrowed from the

Zuni word

ʔa·paču meaning "Navajos" (the plural of

paču "Navajo") (Newman 1958, 1965; de Reuse 1983). .

The Spanish first use the term "Apachu de Nabajo" (Navajo) in the 1620s, referring to people in the

Chama region east of the

San Juan River. By the 1640s, the term was applied to Southern Athabaskan peoples from the Chama on the east to the San Juan on the west.

The tribes' tenacity and fighting skills, probably bolstered by

dime novels, had an impact on Europeans. In early twentieth century Parisian society

Apache essentially meant an outlaw.

Name Many written historical names of Apachean groups recorded by non-Apacheans are difficult to match to modern-day tribes or their sub groups. Many Spanish, French or English speaking authors over the centuries did not distinguish between Apachean and other semi-

nomadic non-Apachean peoples that might pass through the same area. More commonly a name was acquired through a translation of what another group called them. While Anthropologists seem to agree on some traditional major sub grouping of Apaches, they often have used different criteria to name their finer divisions and these do not always match modern Apache groupings. Often groups residing in what is now Mexico are not considered Apaches by some. Adding to an outsider's confusion, an Apachean individual has different ways to identify themselves, such as their band or their clans, depending upon the context.

For example, Grenville Goodwin in the 1930s divided the Western Apaches into five groups (based on his informants' views on dialectal and cultural differences): White Mountain, Cibecue, San Carlos, North Tonto, and South Tonto. Other anthropologists (e.g. Albert Schroeder) consider Goodwin's classification inconsistent with pre-reservation cultural divisions.

Willem de Reuse (2003, 2005, 2006) finds linguistic evidence supporting only three major groupings: White Mountain, San Carlos, and Dilze'e (Tonto) with San Carlos as the most divergent dialect and Dilze'e as a remnant intermediate member of a dialect continuum previously existing between the Western Apache language and Navajo.

John Upton Terrell divides the Apaches into Western and Eastern groups. In the western group he includes

Toboso,

Cholome,

Jocome,

Sibolo,

Pelone,

Manso as having definite Apache connections or names associated with Apaches by the Spanish.

David M. Brugge in a detailed study of New Mexico Church records lists 15 tribal names Spanish used that refer Apaches that represent about 1000 baptisms from 1704 to 1862.

Difficulties in naming The list below is based on Foster &McCollough (2001), Opler (1983b, 1983c, 2001), and de Reuse (1983).

Apaches, current usage generally includes 6 of the 7 major traditional Apachean speaking groups:

Chiricahua,

Jicarilla,

Lipans,

Mescalero,

Plains Apache, and

Western Apache. Historically, the term as also been used for Comanches, Mohaves, Hualapais, and Yavapais.

Arivaipa (also

Aravaipa) is a band of the

San Carlos local group of the Western Apache. Albert Schroeder believes the Arivaipa was a separate section in pre-reservation times.

Arivaipa *is a borrowing (via Spanish) from the

O'odham language. The Arivaipa are known as

Tsézhiné "Black Rock" in the

Western Apache language.

Carlanas (also

Carlanes). An Apache group southeastern Colorado on

Raton Mesa. In 1726, they had joined together with the Cuartelejos and Palomas, and by the 1730s were living with the Jicarilla. It has been suggested that either the Llanero band of the modern Jicarilla or

Mooney's

Dáchizh-ó-zhn Jicarilla division are descendants of the Carlanas, Cuartelejos, and Palomas. The Carlanas as a whole were also called

Sierra Blanca; parts of the group were called

Lipiyanes or

Llaneros. Otherwise, the term has been used synonymously with

Jicarilla in 1812. The

Flechas de Palo might have been a part of or absorbed by the Carlanas (or Cuartelejos).

Chiricahua. One of the 7 major Apachean groups, ranging in southeastern Arizona. (See also

Chíshí.)

Chíshí (also

Tchishi) is a Navajo word meaning "Chiricahua, southern Apaches in general".

Chʼúúkʼanén (also

Čʼókʼánéń,

Čʼó·kʼanén,

Chokonni,

Cho-kon-nen,

Cho Kŭnĕ́,

Chokonen) refers to the

Eastern Chiricahua band of

Morris Opler. The name is an

autonym from the

Chiricahua language.

Cibecue. One of Goodwin's Western Apache groups, living to the North of the Salt River between the Tonto and White Mountain groups. Consisted of Canyon Creek, Carrizo, and Cibecue (proper) bands.

Coyotero usually refers to a southern division of the pre-reservation

White Mountain local group of the Western Apache. However, the name has also been used more widely and can refer to Apaches in general, Western Apaches or a band in the high plains of southern Colorado to Kansas.

Faraones (also

Paraonez,

Pharaones,

Taraones,

Taracones,

Apaches Faraone) is derived from Spanish

Faraón "Pharaoh". Before 1700, the name was vague without a specific referent. Between 1720-1726, it referred to Apaches between the

Rio Grande in the east, the

Pecos River in the west, the area around

Santa Fe in the north, and the

Conchos River in the south. After 1726,

Faraones only referred to the north and central parts of this region. The Faraones probably were, at least in part, part of the modern-day Mescaleros or had merged with the Mescaleros. After 1814, the term

Faraones disappeared having been replaced by

Mescalero.

The

Gileño (also

Apaches de Gila,

Apaches de Xila,

Apaches de la Sierra de Gila,

Xileños,

Gilenas,

Gilans,

Gilanians,

Gila Apache,

Gilleños) was used to refer to several different Apachean and non-Apachean groups at different times.

Gila refers to either the

Gila River or the

Gila Mountains. Some of the Gila Apaches were probably later known as the

Mogollon Apaches, a subdivision of the Chiricahua, while others probably evolved into the Chiricahua proper. However, since the term was used indiscriminately for all Apachean groups west of the

Rio Grande (i.e. in southeast Arizona and western New Mexico), the referent is often unclear. After 1722, Spanish documents start to distinguish between these different groups, in which case

Apaches de Gila refers to Western Apaches living along the Gila River (and thus synonymous with

Coyotero). American writers first used the term to refer to the

Mimbres (another subdivision of the Chiricahua), while later the term was confusingly used to refer to Coyoteros, Mogollones, Tontos, Mimbreños, Pinaleños, Chiricahuas, as well as the non-Apachean

Yavapai (then also known as

Garroteros or

Yabipais Gileños). Another Spanish usage (along with

Pimas Gileños and

Pimas Cileños) referred to the non-Apachean

Pima living on the Gila River.

Jicarilla (from Spanish meaning "little basket"). The

Jicarilla Apache are one of the 7 major Apachean groups and currently live in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Also referenced as living in Texas Panhandle.

Kiowa-Apache. See

Plains Apache.

Llanero is a borrowing from Spanish meaning "plains dweller". The name was historically used to refer to a number of different groups that hunted buffalo seasonally on the Plains, also referenced in eastern New Mexico and western Texas. (See also

Carlanas.)

Lipiyánes (also

Lipiyán,

Lipillanes). An uncertain term, probably of Athabascan origin, that may have been a synonym of

Llanero or

Natagés. This term is not to be confused with

Lipan.

Lipan (also

Ypandis,

Ypandes,

Ipandes,

Ipandi,

Lipanes,

Lipanos,

Lipaines,

Lapane,

Lipanis, etc.). One of the 7 major Apachean peoples. Once in eastern New Mexico and Texas to the southeast to Gulf of Mexico. This term is not to be confused with

Lipiyánes or

Le Panis (French for the

Pawnee). First mentioned in 1718 around the new town of

San Antonio.

Mescalero. The

Mescalero are one of the 7 major Apachean groups, generally living in what is now eastern New Mexico and western Texas.

Mimbreños is an older name that refers to a section of Opler's

Eastern Chiricahua band and to Albert Schroeder's

Mimbres and

Warm Springs Chiricahua bands (Opler lists three Chiricahua bands, while Schroeder lists five) in southwestern New Mexico.

Mogollon was considered by Schroeder a separate pre-reservation Chiricahua band while Opler considered the Mogollon to be part of his

Eastern Chiricahua band in New Mexico.

Náʼįįsha (also

Náʼęsha,

Na´isha,

Naʼisha,

Naʼishandine,

Na-i-shan-dina,

Na-ishi,

Na-e-ca,

Nąʼishą́,

Nadeicha,

Nardichia,

Nadíisha-déna,

Naʼdíʼį́shą́ʼ,

Nądíʼįįshąą,

Naisha) all refer to the Plains Apache (see Kiowa).

Natagés (also

Natagees,

Apaches del Natafé,

Natagêes,

Yabipais Natagé,

Natageses,

Natajes). Term used 1726-1820 to refer to the Faraón, Sierra Blanca, and Siete Ríos Apaches of southeastern New Mexico. In 1745, the Natagés are reported to have consisted of the Mescaleros (around

El Paso and the

Organ Mountains) and the Salineros (around

Rio Salado), but these were probably the same group. After 1749, the term was used synonymously with

Mescalero, which eventually replaced it.

Navajo. The most numerous of the 7 major Apachean groups. General modern usage separates

Navajo people from Apaches.

Pinal (also

Pinaleños). One of the bands of the Goodwin's San Carlos group of Western Apache. Also used along with

Coyotero to refer more generally to one of two major Western Apache divisions. Some Pinaleños were refered to by

Gila Apaches.

Plains Apache. The

Plains Apache (also called

Kiowa-Apache,

Naisha,

Naʼishandine, etc.) are one of the 7 major Apachean groups, generally living in what is now Oklahoma. In historic times, they were found living among the (unrelated)

Kiowa. The term has also been used to refer to any supposed Apachean tribe found on or associated (usually culturally) with the North American Plains.

Ramah. A group of Navajos currently living in the

Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation in New Mexico. (The Navajo name for

Ramah, NM is

Tłʼohchiní meaning "wild onion place").

Querechos referred to by Coronado in 1541, possibly Plains Apaches, at times maybe Navajo. Other early Spanish might have also called them Vaquereo or Llanero.

San Carlos. A Western Apache group that ranged closest to Tucson according to Goodwin. This group consisted of the Apache Peaks, Arivaipa, Pinal, San Carlos (proper) bands.

Tchikun.

Tonto. Goodwin divided into Northern Tonto and Southern Tonto groups. Living in the north and west most areas of the Western Apache groups according to Goodwin. This is north of Phoenix, north of the Verde River. Schroeder has suggested that the Tonto are originally Yavapais who assimilated Western Apache culture. Tonto is one of the major dialects of the Western Apache language. Tonto Apache speakers are traditionally bilingual in Western Apache and

Yavapai. Goodwin's Northern Tonto consisted of Bald Mountain, Fossil Creek, Mormon Lake, and Oak Creek bands; Southern Tonto consisted of the Mazatzal band and unidentified "semi-bands".

Warm Springs were located on upper reaches of Gila River, New Mexico. (See also

Gileño and

Mimbreños.)

Western Apache. In the most common sense, includes Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, White Mountain and San Carlos groups. While these subgroups spoke the same language and had kinship ties, Western Apaches considered themselves as separate from each other, according to Goodwin. Other writers have used this term to refer to all non-Navajo Apachean peoples living west of the Rio Grande (thus failing to distinguish the Chiricahua from the other Apacheans). Goodwin's formulation: "all those Apache peoples who have lived within the present boundaries of the state of Arizona during historic times with the exception of the Chiricahua, Warm Springs, and allied Apache, and a small band of Apaches known as the Apache Mansos, who lived in the vicinity of Tucson" (Goodwin 1942: 55).

White Mountain. The easternmost group of the Western Apache according to Goodwin. Consisted of Eastern White Mountain and Western White Mountain bands.

List of names History The

Apache and

Navajo (Diné) tribal groups of the American Southwest speak related

languages of the language family referred to as

Athabaskan. Other Athabaskan-speaking people in North America reside in an area from Alaska through west-central

Canada, and some groups can be found along the Northwest Pacific Coast.

Linguistic similarities indicate the Navajo and Apache were once a single

ethnic group.

Archaeological and historical evidence seem to suggest the Southern Athabaskan entry into the American Southwest sometime after 1000 AD. Their nomadic way of life complicates accurate dating, primarily because they constructed less-substantial dwellings than other Southwestern groups. (Cordell, pl. 148) They also left behind a more austere set of tools and material goods. This group probably moved into areas that were concurrently or recently abandoned by other cultures. Other Athabaskan speakers, perhaps including the Southern Athabaskan, adapted many of their neighbors' technology and practices in their own cultures. Thus sites where early Southern Athabaskans may have lived are difficult to locate, and even more difficult to firmly identify as culturally Southern Athabaskan.

There are several hypotheses concerning Apachean migrations. One posits that they moved into the Southwest from the

Great Plains. In the early 1500s, these mobile groups lived in tents, hunted

bison and other game, and used dogs to pull

travois loaded with their possessions. Substantial numbers and a wide range were recorded by the Spanish in the 16th Century.

In April 1541, while traveling on the plains east of the

Pueblo region, the

Spanish Francisco Coronado called them "

dog nomads." He wrote:

After seventeen days of travel, I came upon a rancheria of the Indians who follow these cattle (bison). These natives are called Querechos. They do not cultivate the land, but eat raw meat and drink the blood of the cattle they kill. They dress in the skins of the cattle, with which all the people in this land clothe themselves, and they have very well-constructed tents, made with tanned and greased cowhides, in which they live and which they take along as they follow the cattle. They have dogs which they load to carry their tents, poles, and belongings. (ref: Hammond and Rey.)

The Spaniards described Plains dogs as very white, with black spots, and "

not much larger than water spaniels." Plains dogs were slightly smaller than those used for hauling loads by modern northern Canadian peoples. Recent experiments show these dogs may have pulled loads up to 50

lb (20

kg) on long trips, at rates as high as two or three

miles an hour (3 to 5 km/h) (ref: Henderson). This Plains migration theory associates Apachean peoples with the

Dismal River aspect, an

archaeological culture known primarily from ceramics and house remains, dated 1675-1725 excavated in

Nebraska, eastern

Colorado, and western

Kansas.

Another competing theory posits migration south, through the Rocky Mountains, ultimately reaching the Southwest. Only the Plains Apache have any significant Plains cultural influence while all tribes have distinct Athabaskan characteristics. The descriptions of peoples such as the Mountain Querechos and the Apache Vaqueros are vague and could apply to many other Plains tribes and the specific traits of these groups do not seem particularly Apachean. Additionally,

Harry Hoijer's classification of Plains Apache as an Apachean language has been disputed.

When the Spanish arrived in the area, trade between the long established Pueblo peoples and the Southern Athabaskans was well established. They reported the Pueblos exchanged

maize and woven

cotton goods for bison meat, hides and materials for stone tools. Coronado observed Plains people wintering near the Pueblos in established camps. Later Spanish sovereignty over the area disrupted trade between the Pueblos and the now diverging Apache and Navajo groups. The Apache quickly acquired horses, improving their mobility for quick raids on settlements. In addition, as the Pueblo were forced to work Spanish mission lands and care for mission flocks, they had fewer surplus goods to trade with their neighbors. (Cordell, p. 151)

In 1540 Coronado also reported that the modern

Western Apache area as uninhabited. Other Spaniards first mention "Querechos" living west of the

Rio Grande in the 1580s. To some historians this implies the Apaches moved into their current southwestern homelands in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Others historians note that Coronado reported that Pueblos women and children had often been evacuated by the time his party attacked these dwellings and some dwellings had been recently abandoned as he moved up the Rio Grande. This might indicate the semi-nomadic Southern Athabaskans had advance warning about his hostile approach and so they were not seen and reported by the Spanish.

Entry into the Southwest In general, there seemed to be a pattern between the recently arrived Spanish who settled in villages and Apache bands over a few centuries. Both raided and traded with each other. Records of the period seem to indicate that relationships depended upon the specific villages and specific bands that were involved with each other. For example, one band might be friends with one village and raid another. When war happened between the two, the Spanish would send troops, after a battle both sides would "sign a treaty" and both sides would go home. There were no reservations.

The traditional and sometimes treacherous relationships continued between the villages and bands with the independence of Mexico in 1821. By 1835

Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps but some bands were still trading with certain villages. When

Juan José Compas, the leader of the

Mimbreño Apaches, was killed for bounty money in 1837,

Mangas Coloradas or Dasoda-hae (Red Sleeves) became principal chief and war leader and began a series of retaliatory raids against the Mexicans.

When the United States went to war against Mexico, many Apache bands promised U.S. soldiers safe passage through their lands. When the U.S. claimed former territories of Mexico in 1846, Mangas Coloradas signed a peace treaty, respecting them as conquerors of the Mexican's land. An uneasy peace (a centuries old tradition) between the Apache and the now citizens of the United States held until the 1850s, when an influx of gold miners into the

Santa Rita Mountains led to conflict. This period is sometimes called the

Apache Wars.

The United States' concept of a reservation had not been used by the Spanish, Mexicans or other Apache neighbors before. Reservations were often badly managed and bands that had no kinship relationships were forced to live together. There were also no fences to keep people in or out. It was not uncommon for a band to be given permission to leave for a short period of time. Other times a band would leave without permission, to raid, return to their land to forage, or to simply get away. The military usually had forts nearby. Their job was keeping the various bands on the reservations by finding and returning those who left. The reservation policies of the United States kept various Apache bands leaving the reservations (at war) for almost another quarter century.

Most American histories of this era say the final defeat of an Apache band took place when 5,000 troops forced (

Geronimo's) group of 30 to 50 men, women and children to

surrender in

1886. This band and the Chiricahua scouts who tracked them were all sent to military confinement in Florida, and, subsequently, Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

Many books were written on the stories of Hunting and Trapping during the late 1800s. Many of these stories involve Apache raids and agreements with Americans and Mexicans.

Conflict with Mexico and the United States Apache children were taken for adoption by white Americans in programs similar in nature to those involving the

Stolen Generation of Australia.

Post-war period Pre-reservation culture All Apachean peoples lived in extended family units (or

family clusters) that usually lived close together with each nuclear family in separate dwellings. An extended family generally consisted of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, their married daughters, their married daughters' husbands, and their married daughters' children. Thus, the extended family is connected through a lineage of women that live together (that is, matrilocal residence), into which men may enter upon marriage (leaving behind his parents' family). When a daughter was married, a new dwelling was built nearby for her and her husband. Among the Navajo, residence rights are ultimately derived from a head mother. Although the Western Apache usually practiced matrilocal residence, sometimes the eldest son chose to bring his wife to live with his parents after marriage. All tribes practiced

sororate and

levirate marriages.

All Apachean men practiced varying degrees of

avoidance of his wife's close relatives — often strictest between mother-in-law and son-in-law. The degree of avoidance differed in different Apachean groups. The most elaborate system was among the Chiricahua where men must use indirect polite speech toward and were not allowed to be within visual sight of his relatives that he was in an avoidance relationship with. His female Chiricahua relatives also did likewise to him.

Several extended families worked together as a

local group, which carried out certain ceremonies, and economic and military activities. Political control was mostly present at the local group level. Local groups were headed by a chief, a male who had considerable influence over others in the group due to his effectiveness and reputation. The chief was the closest societal role to a leader in Apachean cultures. The office was not hereditary and often filled by members of different extended families. The chief's leadership was only as strong as he was evaluated to be — no group member was ever obliged to follow the chief. The Western Apache criteria for evaluating a good chief included: industriousness, generosity, impartiality, forbearance, conscientiousness, and eloquence in language.

Many Apachean peoples joined together several local groups into

bands. Band organization was strongest among the Chiricahua and Western Apache, while in the Lipan and Mescalero it was weak. The Navajo did not organize local groups into bands perhaps because of the requirements of the sheepherding economy. However, the Navajo did have

the outfit, a group of relatives that was larger than the extended family, but not as large as a local group community or a band.

On the larger level, the Western Apache organized bands into what Grenville Goodwin called

groups. He reported five groups for the Western Apache: Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, San Carlos, and White Mountain. The Jicarilla grouped their bands into

moieties perhaps due to influence from northeastern

Pueblos. Additionally the Western Apache and Navajo had a system of

matrilineal clans that were organized further into

phratries (perhaps due to influence from western Pueblos).

The notion of

tribe in Apachean cultures is very weakly developed essentially being only a recognition "that one owed a modicum of hospitality to those of the same speech, dress, and customs" (Opler 1983a: 369). The seven Apachean tribes had no political unity (despite such protrayals in common perception (Basso 1983)) and often were enemies of each other — for example, the Lipan fought against the Mescalero just as with the

Comanche.

Social organization The Apachean tribes have basically two surprisingly different

kinship term systems: a

Chiricahua type and a

Jicarilla type (Opler 1936b). The Chiricahua type system is used by the Chiricahua, Mescalero, and Western Apache with the Western Apache differing slightly from the other two systems and having some shared similarities with the Navajo system.

The Jicarilla type, which is similar to the

Dakota-

Iroquois kinship systems (see

Iroquois kinship), is used by the Jicarilla, Navajo, Lipan, and Plains Apache. The Navajo system is more divergent having similarities with Chiricahua type system. The Lipan and Plains Apache systems are very similar.

Kinship systems Chiricahua has four different words for

grandparents:

-chú "maternal grandmother",

-tsúyé "maternal grandfather",

-chʼiné "paternal grandmother",

-nálé "paternal grandfather". Additionally, a grandparent's siblings are identified by the same word; thus, one's maternal grandmother, one's maternal grandmother's sisters, and one's maternal grandmother's brothers are all called

-chú. Furthermore, the grandparent terms are reciprocal (i.e. same terms for alternating generations), that is, a grandparent will use the same term to refer to their grandchild in that relationship. For example, a person's maternal grandmother will be called

-chú and that maternal grandmother will also call that person

-chú as well (i.e.

-chú means one's opposite-sex sibling's daughter's child).

Chiricahua cousins are not distinguished from

siblings through kinship terms. Thus, the same word will refer to either a sibling or a

cousin (there are not separate terms for

parallel-cousin and

cross-cousin). Additionally, the terms are used according to the sex of the speaker (unlike the English terms

brother and

sister):

-kʼis "same-sex sibling or same-sex cousin",

-´-ląh "opposite-sex sibling or opposite-sex cousin". This means if one is a male, then one's brother is called

-kʼis and one's sister is called

-´-ląh. If one is a female, then one's brother is called

-´-ląh and one's sister is called

-kʼis. Chiricahuas in a

-´-ląh relationship observed great restraint and respect toward that relative; cousins (but not siblings) in a

-´-ląh relationship may practice total

avoidance.

Two different words are used for each parent according to sex:

-mááʼ "mother",

-taa "father". Likewise, there are two words for a parent's child according to sex:

-yáchʼeʼ "daughter",

-gheʼ "son".

A parent's siblings are classified together regardless of sex:

-ghúyé "maternal aunt or uncle (mother's brother or sister)",

-deedééʼ "paternal aunt or uncle (father's brother or sister)". These two terms are reciprocal like the grandparent/grandchild terms. Thus,

-ghúyé also refers to one's opposite-sex sibling's son or daughter (that is, a person will call their maternal aunt

-ghúyé and that aunt will call them

-ghúyé in return).

Chiricahua Unlike the Chiricahua system, the Jicarilla have only two terms for grandparents according to sex:

-chóó "grandmother",

-tsóyéé "grandfather". There are no separate terms for maternal or paternal grandparents. The terms are also used of a grandparent's siblings according to sex. Thus,

-chóó refers to one's grandmother or one's grandaunt (either maternal or paternal);

-tsóyéé refers to one's grandfather or one's granduncle. These terms are not reciprocal. There is only a single word for grandchild (regardless of sex):

-tsóyí̱í̱.

There two terms for each parent. These terms also refer to that parent's same-sex sibling:

-ʼnííh "mother or maternal aunt (mother's sister)",

-kaʼéé "father or paternal uncle (father's brother)". Additionally, there are two terms for a parent's opposite-sex sibling depending on sex:

-daʼá̱á̱ "maternal uncle (mother's brother)",

-béjéé "paternal aunt (father's sister).

Two terms are used for same-sex and opposite-sex siblings. These terms are also used for

parallel-cousins:

-kʼisé "same-sex sibling or same-sex parallel cousin (i.e. same-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)",

-´-láh "opposite-sex sibling or opposite parallel cousin (i.e. opposite-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)". These two terms can also be used for

cross-cousins. There are also three sibling terms based on the age relative to the speaker:

-ndádéé "older sister",

-´-naʼá̱á̱ "older brother",

-shdá̱zha "younger sibling (i.e. younger sister or brother)". Additionally, there are separate words for cross-cousins:

-zeedń "cross-cousin (either same-sex or opposite-sex of speaker)",

-iłnaaʼaash "male cross-cousin" (only used by male speakers).

A parent's child is classified with their same-sex sibling's or same-sex cousin's child:

-zhácheʼe "daughter, same-sex sibling's daughter, same-sex cousin's daughter",

-gheʼ "son, same-sex sibling's son, same-sex cousin's son". There are different words for an opposite-sex sibling's child:

-daʼá̱á̱ "opposite-sex sibling's daughter",

-daʼ "opposite-sex sibling's son".

Jicarilla

Jicarilla All people in the Apache tribe lived in one of three types of houses. The first of which is the

tipi, for those who lived in the plains. Another type of housing is the

wickiup, an eight-foot tall frame of wood held together with yucca fibers and covered in brush usually in the Apache groups in the highlands. If a family member lived in a wickiup and they died the wickiup would be burned. The final housing is the

hogan, an earthen structure in the desert area that was good for keeping cool in the hot weather of northern Mexico.

Housing Apachean peoples obtained food from four main sources:

The Western Apache diet consisted of 35-40% meat and 60-65% plant foods.

As the different Apachean tribes lived in different environments, the particular types of foods eaten varied according to their respective environment.

hunting wild animals,

gathering wild plants,

growing domesticated plants, and

interaction with neighboring peoples for livestock and agricultural products (through raiding or trading).

Food Hunting was done primarily by men, although there were sometimes exceptions depending on animal and culture (e.g. Lipan women could help in hunting rabbits and Chiricahua boys were also allowed to hunt rabbits).

Hunting often had elaborate preparations, such as fasting and religious rituals performed by medicine men before and after the hunt. In Lipan culture, since deer were protected by Mountain Spirits, great care was taken in Mountain Spirit rituals in order to ensure smooth deer hunting.

The Western Apache hunted deer and

pronghorns (antelope) mostly in the ideal late fall season. After the meat was smoked into jerky around November, a migration from the farm sites along the stream banks in the mountains to winter camps in the

Salt,

Black, and

Gila river valleys.

The primary game of the Chiricahua was the deer followed by pronghorn (antelope). Lesser game included:

cottontail rabbits (but not

jack rabbits), opossums, squirrels, surplus horses, surplus mules,

wapiti elk, wild cattle,

wood rats.

The Mescalero primarily hunted deer. Other animals hunted include:

bighorn sheep, buffalo (for those living closer to the plains), cottontail rabbits, elk, horses, mules, opossums, pronghorn, wild steers, and wood rats. Beavers, minks, muskrats, and weasels were also hunted for their hides and body parts but were not eaten.

The principle game of the Jicarilla was bighorn sheep, buffalo, deer, elk, and pronghorn. Other game animals include: Beaver, bighorn sheep, chief hares, chipmunks, doves, ground hogs, grouse, peccaries, porcupines, prairie dogs, quail, rabbits, skunks, snow birds, squirrels, turkeys, wood rats. Burros and horses were only eaten in emergencies. Minks, weasels, wildcats, and wolves were not eaten but hunted for their body parts.

The main food of the Lipan was the buffalo with a 3-week hunt during the fall and smaller scale hunts continuing until the spring. The second most utilized animal was deer. Fresh deer blood was drunk for good health. Other animals included: beavers, bighorns, black bears, burros, ducks, elk, fish, horses, mountain lions, mourning doves, mules, prairie dogs, pronghorns, quail, rabbits, squirrels, turkeys, turtles, wood rats. Skunks were eaten only in emergencies.

Plains Apache hunters pursued primarily buffalo and deer. Other hunted animals were badgers, bears, beavers, geese, fowls (of various varieties), opossums, otters, rabbits, and turtles.

Eating certain animals was taboo. Although different cultures had different taboos, some common examples of taboo animals included: bears, peccaries, turkeys, fish, snakes, insects, owls, and coyotes. An example of taboo differences: the black bear was a part of the Lipan diet (although not as common as buffalo, deer, or antelope), but the Jicarilla never ate bear as it was considered an evil animal. Some taboos were a regional phenomena, such as of eating fish, which was taboo throughout the southwest (e.g. in certain pueblos) and considered to be snake-like (an evil animal) in physical appearance (Brugge 1983: 494; Landar 1960).

A common practice among Southern Athabascan hunters was the distribution of successfully slaughtered game. For example, among the Mescalero a hunter was expected to share as much as one half of his kill with a fellow hunter and with needy persons back at the camp.

Hunting The gathering of plants and other foodstuffs was primarily a female chore. However, in certain activities, such as the gathering of heavy

agave crowns, men helped. Numerous plants were used for medicine and religious ceremonies in addition their nutrional usage. Other plants (not mentioned here) were utilized for only their religious or medicinal value. Below are listed (but not exhaustively) some of the items gathered by different Southern Athabascan groups.

In May, the Western Apache baked and dried agave crowns that were pounded into pulp and formed into rectangular cakes. At the end of June and beginning of July,

saguaro,

prickly pear, and

cholla fruits were gathered. In July and August,

mesquite beans,

Spanish bayonet fruit, and

Emory oak acorns were gathered. In late September, gathering was stopped as attention moved toward harvesting cultivated crops. In late fall,

juniper berries and

pinyon nuts were gathered.

The most important plant food used by the Chiricahua was the

Century plant (also known as

mescal or agave). The crowns (the

tuberous base portion) of this plant (which were baked in large underground ovens and sun-dried) and also the

shoots were used. Other plants utilized by the Chiricahua include: acorns,

agarita berries,

cactus fruits (of various species),

chokecherries, grass seeds (of various varieties),

greens (of various varieties), juniper berries,

locust blossoms, mesquite beans,

mulberries, onions, pine inner bark (used as a sweetner), pine nuts, pinyon nuts, potatoes, prickly pears, raspberries,

screwbean fruit, strawberries,

sumac berries, sunflower seeds,

tule rootstocks, walnuts,

wild grapes,

yucca blossoms, yucca fruit, and yucca stalks. Other items include: honey from ground hives and hives found within agave,

sotol, and yucca plants.

The abundant agave (mescal) was also important to the Mescalero, who gathered the crowns in late spring after reddish flower stalks appeared. The smaller sotol crowns were also important. Both crowns of both plants were baked and dried. Other plants include: acorns, agarita berries,

amole stalks (roasted & peeled),

aspen inner bark (used as a sweetner),

bear grass stalks (roasted & peeled),

box elder inner bark (used as a sweetner), box elder sap (used as a sweetner), cactus fruits (of various varieties),

cattail rootstocks, chokecherries,

currants,

datil fruit, datil flowers,

dropseed grass seeds (used for

flatbread),

elderberries,

gooseberries, grapes,

hackberries,

hawthorne fruit,

hops (used as condiment),

horsemint (used as condiment), juniper berries,

Lamb's-quarters leaves, locust flowers, locust pods, mesquite pods, mint (used as condiment), mulberries,

pennyroyal (used as condiment),

pigweed seeds (used for flatbread), pine inner bark (used as a sweetner), pinyon pine nuts, prickly pear fruit (dethorned & roasted),

purslane leaves, raspberries, sage (used as condiment), screwbeans,

sedge tubers,

shepherd's purse leaves, strawberries, sunflower seeds,

tumbleweed seeds (used for flatbread),

vetch pods, walnuts,

western white pine nuts,

western yellow pine nuts, white

evening primrose fruit,

wild celery (used as condiment),

wild onion (used as condiment), wild pea pods, wild potatoes, and

wood sorrel leaves.

The Jicarilla used acorns, chokecherries, juniper berries, mesquite beans, pinyon nuts, prickly pear fruit, and yucca fruit, as well as many different kinds of other fruits, acorns, greens, nuts, and seed grasses.

The most important plant food used by the Lipan was agave (mescal). Another important plant was sotol. Other plants utilized by the Lipan include: agarita, blackberries, cattails, devil's claw, elderberries, gooseberries, hackberries, hawthorn, juniper, Lamb's-quarters, locust, mesquite, mulberries,

oak,

palmetto, pecan, pinyon, prickly pears, raspberries, screwbeans, seed grasses, strawberries, sumac, sunflowers, Texas

persimmons, walnuts, western yellow pine, wild cherries, wild grapes, wild onions, wild plums, wild potatoes,

wild roses, yucca flowers, and yucca fruit. Other items include: salt obtained from caves and honey.

Plants utilized by the Plains Apache include: chokecherries, blackberries, grapes,

prairie turnips, wild onions, and wild plums. Numerous other fruits, vegetables, and tuberous roots were also used.

Non-domesticated plants & other foodstuffs

Non-domesticated plants & other foodstuffs The different Apachean groups varied greatly with respect to growing domesticated plants. The Navajo practiced the most crop cultivation while the Western Apache, Jicarilla, and Lipan also doing so but to a lesser extent. The one Chiricahua band (of Opler's) and Mescalero practiced very little cultivation. The other two Chiricahua bands and the Plains Apache did not grow any crops.

Crop cultivation Although not distinguished by Europeans or Euro-Americans, all Apachean tribes made clear distinctions between raiding (for profit) and war. Raiding was done with small parties with a specific economic target. Warfare was waged with large parties (often using clan members) with the sole purpose of retribution.

Trading and raiding Apachean

religious stories relate two

culture heros (one of the sun/fire,

Killer-Of-Enemies/Monster Slayer, and one of water/moon/thunder,

Child-Of-The-Water/Born For Water) that destroy a number of creatures (including the

Vagina dentata) that are harmful to humankind. Another story is of a hidden ball game where good and evil animals decide whether or not the world should be forever dark.

Coyote, the

trickster, is an important being that usually has inappropriate behavior (such as marrying his own daughter, etc.). The Navajo, Western Apache, Jicarilla, and Lipan have an emergence story while this is lacking in the Chiricahua and Mescalero (Opler 1983a: 368-369).

Most Southern Athabascan gods are personified natural forces that run through the universe and are used for human purposes through ritual ceremonies. These ceremonies are known by priests or can be acquired by direct revelation to the individual. Different Apachean cultures had different views of ceremonial practice. Most Chiricahua and Mescalero ceremonies were learned by personal religious visions while the Jicarilla and Western Apache used standardized rituals as the more central ceremonial practice. Important standardized ceremonies include the puberty ceremony (sunrise dance) of young women, Navajo chants, Jicarilla long-life ceremonies, and Plains Apache sacred-bundle ceremonies.

Certain animals are considered spiritually evil and are prone to cause sickness: owls, snakes, bears, coyotes.

Many Apachean ceremonies use masked representations of religious spirits.

Sandpainting is important to the Navajo, Western Apache, and Jicarilla. Both the use of masks and sandpainting is believed to be a product of

cultural diffusion from neighboring Pueblo cultures (Opler 1983a: 372-373).

The Apaches participate in many spiritual dances including the rain dance, a harvest and crop dance, and a spirit dance. These dances were mostly for enriching their food resources.

Religion Main article: Southern Athabascan languages Notable Apache

Balls per over

Balls per over The future

The future

Education

Education

Common National Diplomas

Common National Diplomas History

History

Famous and infamous

Famous and infamous

radical

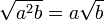

radical  The principal nth root of a real number a is the unique real number b which is an nth root of a and is of the same sign as a. Note that if n is

The principal nth root of a real number a is the unique real number b which is an nth root of a and is of the same sign as a. Note that if n is  Fundamental operations

Fundamental operations ) depicts surds, with the upper line above the expression called the vinculum. A cube root takes the form:

) depicts surds, with the upper line above the expression called the vinculum. A cube root takes the form: , when expressed using

, when expressed using  ,

,

![sqrt[6>{a^6b^4} = sqrt[3cdot 2]{a^2a^2a^2b^2b^2} = sqrt[3]{a^3b^2} = asqrt[3]{b^2}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/0/e/b0e0bad6e8c3c0834ed47bb8fbacddd8.png)

![sqrt[n>{a^m b} = a^{frac{m}{n}}sqrt[n]{b}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/3/7/b372247805535b8f54dc58e199d59b32.png)

Working with surds

Working with surds

.

. for

for  , where

, where  for

for  Jicarilla

Jicarilla Non-domesticated plants & other foodstuffs

Non-domesticated plants & other foodstuffs